Amazon Prime Free Trial

FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button and confirm your Prime free trial.

Amazon Prime members enjoy:- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited FREE Prime delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new:

-13% $15.61$15.61

Ships from: Amazon.com Sold by: Amazon.com

Save with Used - Good

$6.86$6.86

Ships from: Amazon Sold by: Books For You Today

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required.

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Audible sample

Audible sample Follow the author

OK

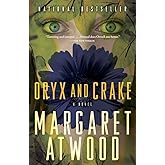

Cat's Eye Paperback – January 20, 1998

Purchase options and add-ons

Disturbing, humorous, and compassionate, Cat’s Eye is the story of Elaine Risley, a controversial painter who returns to Toronto, the city of her youth, for a retrospective of her art. Engulfed by vivid images of the past, she reminisces about a trio of girls who initiated her into the the fierce politics of childhood and its secret world of friendship, longing, and betrayal. Elaine must come to terms with her own identity as a daughter, a lover, an artist, and a woman—but above all she must seek release form her haunting memories.

- Print length480 pages

- LanguageEnglish

- PublisherVintage

- Publication dateJanuary 20, 1998

- Dimensions5.09 x 1 x 7.99 inches

- ISBN-100385491026

- ISBN-13978-0385491020

- Lexile measure850L

From #1 New York Times bestselling author Colleen Hoover comes a novel that explores life after tragedy and the enduring spirit of love. | Learn more

Frequently bought together

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Editorial Reviews

Review

"A brilliant, three-dimensional mosaic...the story of Elaine's childhood is so real and heartbreaking you want to stand up in your seat and cheer." —Boston Sunday Globe

"Stunning...Atwood conceives Elaine with a poet's transforming fire; and delivers her to us that way, a flame inside an icicle." —Los Angeles Times

"Nightmarish, evocative, heartbreaking." —The New York Times Book Review

"The best book in a long time on female friendships... Cat's Eye is remarkable, funny, and serious, brimming with uncanny wisdom." —Cosmopolitan

From the Inside Flap

From the Back Cover

About the Author

Atwood has won numerous awards including the Arthur C. Clarke Award for Imagination in Service to Society, the Franz Kafka Prize, the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade, the PEN USA Lifetime Achievement Award and the Dayton Literary Peace Prize. In 2019 she was made a member of the Order of the Companions of Honour for services to literature. She has also worked as a cartoonist, illustrator, librettist, playwright and puppeteer. She lives in Toronto, Canada.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

1

Time is not a line but a dimension, like the dimensions of space. If you can bend space you can bend time also, and if you knew enough and could move faster than light you could travel backward in time and exist in two places at once.

It was my brother Stephen who told me that, when he wore his raveling maroon sweater to study in and spent a lot of time standing on his head so that the blood would run down into his brain and nourish it. I didn’t understand what he meant, but maybe he didn’t explain it very well. He was already moving away from the imprecision of words.

But I began then to think of time as having a shape, something you could see, like a series of liquid transparencies, one laid on top of another. You don’t look back along time but down through it, like water. Sometimes this comes to the surface, sometimes that, sometimes nothing. Nothing goes away.

2

“Stephen says time is not a line,” I say. Cordelia rolls her eyes, as I knew she would.

“So?” she says. This answer pleases both of us. It puts the nature of time in its place, and also Stephen, who calls us “the teenagers,” as if he himself is not one. Cordelia and I are riding on the streetcar, going downtown, as we do on winter Saturdays. The streetcar is muggy with twice-breathed air and the smell of wool. Cordelia sits with nonchalance, nudging me with her elbow now and then, staring blankly at the other people with her gray-green eyes, opaque and glinting as metal. She can outstare anyone, and I am almost as good. We’re impervious, we scintillate, we are thirteen.

We wear long wool coats with tie belts, the collars turned up to look like those of movie stars, and rubber boots with the tops folded down and men’s work socks inside. In our pockets are stuffed the kerchiefs our mothers make us wear but that we take off as soon as we’re out of their sight. We scorn head coverings. Our mouths are tough, crayon-red, shiny as nails. We think we are friends.

On the streetcars there are always old ladies, or we think of them as old. They’re of various kinds. Some are respectably dressed, in tailored Harris tweed coats and matching gloves and tidy no-nonsense hats with small brisk feathers jauntily at one side. Others are poorer and foreign-looking and have dark shawls wound over their heads and around their shoulders. Others are bulgy, dumpy, with clamped self-righteous mouths, their arms festooned with shopping bags; these we associate with sales, with bargain basements. Cordelia can tell cheap cloth at a glance. “Gabardine,” she says. “Ticky-tack.”

Then there are the ones who have not resigned themselves, who still try for an effect of glamour. There aren’t many of these, but they stand out. They wear scarlet outfits or purple ones, and dangly earrings, and hats that look like stage props. Their slips show at the bottoms of their skirts, slips of unusual, suggestive colors. Anything other than white is suggestive. They have hair dyed straw-blond or baby-blue, or, even more startling against their papery skins, a lusterless old-fur-coat black. Their lipstick mouths are too big around their mouths, their rouge blotchy, their eyes drawn screw-jiggy around their real eyes. These are the ones most likely to talk to themselves. There’s one who says “mutton, mutton,” over and over again like a song, another who pokes at our legs with her umbrella and says “bare naked.”

This is the kind we like best. They have a certain gaiety to them, a power of invention, they don’t care what people think. They have escaped, though what it is they’ve escaped from isn’t clear to us. We think that their bizarre costumes, their verbal tics, are chosen, and that when the time comes we also will be free to choose.

“That’s what I’m going to be like,” says Cordelia. “Only I’m going to have a yappy Pekinese, and chase kids off my lawn. I’m going to have a shepherd’s crook.”

“I’m going to have a pet iguana,” I say, “and wear nothing but cerise.” It’s a word I have recently learned.

***

Now I think, what if they just couldn’t see what they looked like? Maybe it was as simple as that: eye problems. I’m having that trouble myself now: too close to the mirror and I’m a blur, too far back and I can’t see the details. Who knows what faces I’m making, what kind of modern art I’m drawing onto myself? Even when I’ve got the distance adjusted, I vary. I am transitional; some days I look like a worn-out thirty-five, others like a sprightly fifty. So much depends on the light, and the way you squint.

I eat in pink restaurants, which are better for the skin. Yellow ones turn you yellow. I actually spend time thinking about this. Vanity is becoming a nuisance; I can see why women give it up, eventually. But I’m not ready for that yet.

Lately I’ve caught myself humming out loud, or walking along the street with my mouth slightly open, drooling a little. Only a little; but it may be the thin edge of the wedge, the crack in the wall that will open, later, onto what? What vistas of shining eccentricity, or madness?

There is no one I would ever tell this to, except Cordelia. But which Cordelia? The one I have conjured up, the one with the rolltop boots and the turned-up collar, or the one before, or the one after? There is never only one, of anyone.

If I were to meet Cordelia again, what would I tell her about myself? The truth, or whatever would make me look good?

Probably the latter. I still have that need.

I haven’t seen her for a long time. I wasn’t expecting to see her. But now that I’m back here I can hardly walk down a street without a glimpse of her, turning a comer, entering a door. It goes without saying that these fragments of her-a shoulder, beige, camel’s-hair, the side of a face, the back of a leg-belong to women who, seen whole, are not Cordelia.

I have no idea what she would look like now. Is she fat, have her breasts sagged, does she have little gray hairs at the comers of her mouth? Unlikely: she would pull them out. Does she wear glasses with fashionable frames, has she had her lids lifted, does she streak or tint? All of these things are possible: we’ve both reached that borderline age, that buffer zone in which it can still be believed such tricks will work if you avoid bright sunlight.

I think of Cordelia examining the growing pouches under her eyes, the skin, up close, loosened and crinkled like elbows. She sighs, pats in cream, which is the right kind. Cordelia would know the right kind. She takes stock of her hands, which are shrinking a little, warping a little, as mine are. Gnarling has set in, the withering of the mouth; the outlines of dewlaps are beginning to be visible, down toward the chin, in the dark glass of subway windows. Nobody else notices these things yet, unless they look closely; but Cordelia and I are in the habit of looking closely.

She drops the bath towel, which is green, a muted sea-green to match her eyes, looks over her shoulder, sees in the mirror the dog’s-neck folds of skin above the waist, the buttocks drooping like wattles, and, turning, the dried fern of hair. I think of her in a sweatsuit, sea-green as well, working out in some gym or other, sweating like a pig. I know what she would say about this, about all of this. How we giggled, with repugnance and delight, when we found the wax her older sisters used on their legs, congealed in a little pot, stuck full-of bristles. The grotesqueries of the body were always of interest to her.

I think of encountering her without warning. Perhaps in a worn coat and a knitted hat like a tea cosy, sitting on a curb, with two plastic bags filled with her only possessions, muttering to herself. Cordelia! Don’t you recognize me? I say. And she does, but pretends not to. She gets up and shambles away on swollen-feet, old socks poking through the holes in her rubber boots, glancing back over her shoulder.

There’s some satisfaction in that, more in worse things. I watch from a window, or a balcony so I can see better, as some man chases Cordelia along the sidewalk below me, catches up with her, punches her in the ribs—I can’t handle the face—throws her down. But I can’t go any farther.

Better to switch to an oxygen tent. Cordelia is unconscious. I have been summoned, too late, to her hospital bedside. There are flowers, sickly smelling, wilting in a vase, tubes going into her arms and nose, the sound of terminal breathing. I hold her hand. Her face is puffy, white, like an unbaked biscuit, with yellowish circles under the closed eyes. Her eyelids don’t flicker but there’s a faint twitching of her fingers, or do I imagine it? I sit there wondering whether to pull the tubes out of her arms, the plug out of the wall. No brain activity, the doctors say. Am I crying? And who would have summoned me?

Even better: an iron lung. I’ve never seen an iron lung, but the newspapers had pictures of children in iron lungs, back when people still got polio. These pictures-the iron lung a cylinder, a gigantic sausageroll of metal, with a head sticking out one end of it, always a girl’s head, the hair flowing across the pillow, the eyes large, nocturnal-fascinated me, more than stories about children who went out on thin ice and fell through and were drowned, or children who played on the railroad tracks and had their arms and legs cut off by trains. You could get polio without knowing how or where, end up in an iron lung without knowing why. Something you breathed in or ate, or picked up from the dirty money other people had touched. You never knew.

The iron lungs were used to frighten us, and as reasons why we couldn’t do things we wanted to. No public swimming pools, no crowds in summer. Do you want to spend the rest of your life in an iron lung? they would say. A stupid question; though for me such a life, with its inertia and pity, had its secret attractions.

Cordelia in an iron lung, then, being breathed, as an aceordian is played. A mechanical wheezing sound comes from around her. She is fully conscious, but unable to move or speak. I come into the room, moving, speaking. Our eyes meet.

Product details

- Publisher : Vintage (January 20, 1998)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 480 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0385491026

- ISBN-13 : 978-0385491020

- Lexile measure : 850L

- Item Weight : 2.31 pounds

- Dimensions : 5.09 x 1 x 7.99 inches

- Best Sellers Rank: #116,269 in Books (See Top 100 in Books)

- #294 in Literary Criticism & Theory

- #1,635 in Psychological Fiction (Books)

- #8,197 in Literary Fiction (Books)

- Customer Reviews:

About the author

Margaret Atwood is the author of more than fifty books of fiction, poetry and critical essays. Her novels include Cat's Eye, The Robber Bride, Alias Grace, The Blind Assassin and the MaddAddam trilogy. Her 1985 classic, The Handmaid's Tale, went back into the bestseller charts with the election of Donald Trump, when the Handmaids became a symbol of resistance against the disempowerment of women, and with the 2017 release of the award-winning Channel 4 TV series. ‘Her sequel, The Testaments, was published in 2019. It was an instant international bestseller and won the Booker Prize.’

Atwood has won numerous awards including the Booker Prize, the Arthur C. Clarke Award for Imagination in Service to Society, the Franz Kafka Prize, the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade and the PEN USA Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2019 she was made a member of the Order of the Companions of Honour for services to literature. She has also worked as a cartoonist, illustrator, librettist, playwright and puppeteer. She lives in Toronto, Canada.

Photo credit: Liam Sharp

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Learn more how customers reviews work on AmazonCustomers say

Customers find the book relatable and fascinating. They praise the writing quality as well-written and outstanding. The characters are described as insightful and deep. Many appreciate the gender identity exploration and intersection of lives of women. The human experience is evoked through the descriptions of feelings and surroundings. While some find the length too long, others consider it an economical way to build a library.

AI-generated from the text of customer reviews

Customers find the book engaging. They describe it as an introspective, relatable story about trauma. The narrative resonates with them and reflects an understanding of myth, humanities, and human experience. While some readers did not connect with the main character, the overall idea of the story is good and grabs their attention throughout the book.

"...most enjoyed were the way Atwood presents memory and the descriptions of Elaine’s paintings. Memory is an obvious but really interesting theme here...." Read more

"...I both hated and loved this book. Loved it for her beautiful, intricate, evocative use of language ... and hated it because it made me so..." Read more

"...Combined with the visual images of the art showing that depicts many of those childhood moments, the language in Atwood's story had me rereading..." Read more

"...I enjoy well-written, emotionally evocative stories that stay with me and make me want to read more works by the author...." Read more

Customers appreciate the writing quality of the book. They find it well-written and engaging, with beautiful prose that jumps off the page. The book is described as an easy read with concise details and precise language. Readers praise the author's skill in storytelling, describing her words as insightful and bringing their lives to life.

"...It’s an “easy read” in a way that some of her other works are not, but as with the other pieces, reading and thinking about Atwood’s characters and..." Read more

"...Loved it for her beautiful, intricate, evocative use of language ... and hated it because it made me so uncomfortable...." Read more

"...in Atwood's story had me rereading parts because of the sheer magic of the words...." Read more

"...I enjoy well-written, emotionally evocative stories that stay with me and make me want to read more works by the author...." Read more

Customers appreciate the book's character study. They find the characters engaging, with depth and psychological insights. The descriptions of their clothes, games, and interactions are also appreciated.

"...It's like a psychological character study. It's the feelings that are evoked. Everything is full of descriptions, the meaning belongs to the reader...." Read more

"Margaret Atwood's precision of language, turn of phrase and insightful characterisation make this novel a wonderful.read...." Read more

"The characters are all interesting and grab you throughout the book. They reappear and remind you of their past and what to expect of the future." Read more

"...a piece that resolves... And then concludes, achieving such striking depth of characters that you just want to re-read it as well as re-reading your..." Read more

Customers appreciate the book's gender identity. They find it female-centered, with all the contradictions and nuances of being a girl. The novel dissects and reassembles traditional gender roles through the main character's art. It provides an interesting look at the intersecting lives of women and how our earliest interactions inform our lives.

"...This one is strikingly female, with all of the contradictions, complications, and nuances of being a girl...." Read more

"...a brilliant introspective novel that dissects and reassembles traditional gender roles through the art of the main character Elaine...." Read more

"...She's a very distinct voice that is quite important, especially for women. Her intellect and ability to see people is nearly superhuman...." Read more

"A cool look at the intersecting lives of women and how our earliest interactions inform our lives thereafter...." Read more

Customers enjoy the book's experience. They find it a deeply personal and emotional read that evokes feelings. The writing is beautiful and allows readers to feel and visualize the surroundings.

"...It's like a psychological character study. It's the feelings that are evoked. Everything is full of descriptions, the meaning belongs to the reader...." Read more

"...wrapped around a deep understanding of myth, humanities, and human experience. This may be my favorite book of all time." Read more

"About as intimate and true as anything I've read, an inward out-of-body experience. Painterly: Wyeth, Brueghel, Chagall...." Read more

"So many fascinating images and emotional experiences. Childhood exposed with all its mysteries. Perfect meld of art and literature. Read this" Read more

Customers appreciate the book's value for money. They say it's an economical way to build a library.

"...I'm almost finished with the second of the trilogy. Great prices!..." Read more

"This book arrived on time and was priced just right. The quality description was spot on." Read more

"...The library ran out of copies and this was certainly an inexpensive solution." Read more

"Great Seller!!!..." Read more

Customers have different views on the pacing of the book. Some find it fresh and illuminating, while others find it boring and lacking substance. The narrative is described as straightforward and seamlessly interwoven. However, some readers feel the obsession lacks substance and there is little point to it all.

"...’s because Cat’s Eye appears, at least on the surface, to be a more straightforward, less complex narrative...." Read more

"...and interconnections, and all of them are interwoven delicately and seamlessly...." Read more

"...is understandable and empathetic, but her continuing obsession as an adult lacks substance and doesn't really have a point...." Read more

"...It’s a good look at the cruelties children visit in each other and the impact of these experiences on who we become...." Read more

Customers dislike the book's length. They say it is long and not a page-turner in the traditional sense.

"...Be prepared, it is long and is not a page turner in the traditional sense, but it will leave you wondering and reflecting." Read more

"...(Oryx and Crake, The Edible Woman) I feel the book was too long for the material covered...." Read more

"Rather interesting but much too long, with some boring passages." Read more

Reviews with images

Great Seller!!!

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. Please try again later.

- Reviewed in the United States on November 28, 2015Cat’s Eye is one of Margaret Atwood’s more popular novels, as I learned after reading The Blind Assassin (and its reviews) several months ago. Comparatively speaking, I imagine it’s because Cat’s Eye appears, at least on the surface, to be a more straightforward, less complex narrative. I became a fan of Atwood ten or eleven years ago after reading The Handmaid’s Tale and continued to enjoy her poetry and short stories before going on a sort of Atwood novel mini-binge lately (Blind Assassin, Robber Bride, and now Cat’s Eye – up next is Alias Grace). I found Cat’s Eye much more engaging than The Robber Bride, though I wouldn’t rate it quite as high as The Blind Assassin. Something that really appealed to me about Blind Assassin is its resistance to “genre” – at least as far as any novel has to fit solidly into one or two established genres. Except for The Handmaid’s Tale, I think Cat’s Eye may be the easiest to categorize, though Atwood’s work defies easy labeling, and that’s what makes it so great and so interesting. Cat’s Eye is definitely a bildungsroman/coming-of-age novel as well as a kunstlerroman/artist’s novel. There are a couple of complicating factors: for one, Atwood’s protagonist Elaine comes of age as a woman and as a female artist amidst the early feminist movement, and two, the reader is left unsure whether Elaine sees her formative experiences as ultimately making her a better person. This is not to say that all coming-of-age narratives dramatize the protagonist’s maturation as positive, but there is a tendency in these stories toward upward progress. In Elaine’s case, however, it seems that the formative experiences of her childhood damaged her in way that she has never quite overcome. As is standard in Atwood’s work, the character’s formative experiences are also inextricably linked to the fact that she is female.

Elaine describes her childhood in a couple of stages and locates a firm turning point. As a young girl, her main companion was her older brother; the two children spent most of their time with their father in the wilderness collecting specimens, but both parents and Elaine’s brother seem to be rather laidback, living according to their own internal compasses and unaffected by the outside world. Once Elaine’s family settles into a community in Toronto and Elaine attends a local school, she feels the need to become friends with other young girls (the school separates the students by gender for many activities). It is over the course of these first years at the school that Elaine learns of the artificiality, deception, and cruelty of which girls and women are capable. These lessons come not only from her young friends but also (in some ways even more so) from their mothers, as well as from the female teachers at school. For example, Elaine’s friend Grace’s mother, Mrs. Smeath, is a central figure in the adult Elaine’s controversial (possibly feminist?) paintings. It is the Smeath family that attempts to sort of socialize and Christianize the young Elaine, and it is from this family but mostly from Mrs. Smeath that Elaine receives the harshest judgment – Elaine is not a “normal girl” or a “good girl” because she does not conform to Mrs. Smeath’s narrow idea of what is acceptable and proper for young girls like her daughter Grace. This is not because of any intentional rebellion on Elaine’s part; she simply behaves how she always has, perhaps modeling the behavior of her own parents, or perhaps just instinctually because she never has the kind of parents who push norms (gender or otherwise) onto their daughter. Either way, it is her exposure to the other girls and their families that makes Elaine doubt herself, causing her to feel like something is wrong with her. This is something Elaine internalizes and it continues to haunt her entire life. Another young girl, Cordelia, becomes the ringleader of the group, and she is described as an evil little dictator that Elaine can nonetheless not help but to obey and cater to. After a particularly traumatic incident, directed by Cordelina and in which Elaine’s life was actually in serious danger, Elaine distances herself from these other girls as she ages, she seems to forget the painful experiences of her girlhood, and she becomes harder, more nonchalant and sarcastic, obviously as a defense mechanism. In an interesting reversal, when the girls become teenagers, and after years of virtually no contact between the two girls, Cordelia’s mother asks Elaine if she will walk to high school with Cordelia (she has been kicked out of the other school she was attending and now must attend Elaine’s school). Seemingly unfazed, Elaine agrees to this and senses a shift in the power differential between the two girls. From Elaine’s perspective, Cordelia is now damaged in some way, even though Elaine formerly thought of Cordelia and her influence as invincible. Over the course of their teenage years, Elaine seems to view the friendship casually, apparently not remembering the former trauma inflicted on her by Cordelia. Eventually, Cordelia ends up in a mental hospital and Elaine’s relationship with her is sporadic. However, Cordelia seems to always be on Elaine’s mind. When Elaine as a middle-aged-woman returns to Toronto for her art retrospective, she expects (hopes?) to see Cordelia; it’s as though the city is haunted by Cordelia’s memory but of course the reader does not know why at the beginning of the novel. It is only gradually that Elaine’s memories unfold and it is not until Elaine returns to Toronto and to the bridge where she nearly froze to death as a child (in an attempt to appease Cordelia) that she (and we as readers) understand why Cordelia has continued to exert such a power over Elaine after all this time, even after Elaine has grown into what she herself would probably call “a stronger person.” For example, the judgment cast upon Elaine by Cordelia, the other girls, and their mothers is later reflected in the insecurity Elaine feels around other women, particularly feminist artists, at other times in her adult life.

As in The Robber Bride, it’s the relationships between female characters that interest Atwood and by extension the reader. It’s for this reason that the novel’s intensity wanes a bit as Elaine tells the story of her young adulthood, her affair with Jozef, and her marriage to Jon (and later Ben, who is barely mentioned). Ultimately, men are a peripheral presence in the novel and Elaine is mostly occupied by her memories of relationships with other women/girls. In a novel suffused by religious imagery (i.e. the Virgin Mary in both Elaine’s personal history and the art history course she takes at the university) more so than I’ve noticed otherwise in Atwood’s work, Elaine’s return to the bridge to confront the decades-old memory of what happened there reads like an exorcism (an interesting reversal of what happened during the original scene when Elaine was a child – she imagines the Virgin Mary appears to her and encourages her to get up, otherwise she may have frozen to death). Elaine sees the childlike figure of Cordelia and seems to feel like she understands Cordelia’s own insecurity and Atwood here returns to the motif that girls/women are almost always playing parts that they think they are supposed to be playing; she seems to forgive Cordelia and implicitly blame something bigger than that one little girl, even though Elaine is hesitant to declare herself a feminist painter at the start of the novel. This is not to say that the novel ends “happily.” After Elaine has apparently exorcised Cordelia’s influence, she feels a strange emptiness when looking at the scene of the childhood trauma inflicted on her by Cordelia. This reminds me of the ending of The Robber Bride, when the three women spread Zenia’s ashes from the ferryboat. There’s something about the tension in these relationships between female “friends” that is central to their lives and their identities; without that tension, there is relief, maybe, but there is also a sense of loss. This strikes characters and readers both as unexpected but also inevitable.

This is an exceptional novel that leaves readers’ minds lingering over what they’ve just read. Cat’s Eye is certainly more complex than it appears to be on the surface. A couple of features of the novel that I most enjoyed were the way Atwood presents memory and the descriptions of Elaine’s paintings. Memory is an obvious but really interesting theme here. Once Elaine begins narrating her childhood, she does so as though all of her memories are totally clear, but when she gets into her adolescence and her teenage years, she refers to her childhood (the same one she just narrated with clarity) in a vague way that indicates different levels of understanding at different times in her life. This is just a little touch on Atwood’s part that adds nuance and also makes the reader question Elaine’s reliability (or at least become aware of the fact that we are reading a story from one very specific lens). The question of narrative reliability is always there in Atwood’s fiction; however, I did not find that it affected my sympathy for Elaine’s character. Finally, I really enjoyed reading about Elaine’s artworks, which are not described in detail until late in the novel. After having read through Elaine’s history and memories, it was cool to see how she worked her experiences into her art; thinking about how Elaine formed those events, people, and memories into her paintings also gives the reader another perspective on how Elaine processed and reacted to past experiences.

I would highly recommend Cat’s Eye, especially to someone who hasn’t read Atwood yet or is new to her work. It’s an “easy read” in a way that some of her other works are not, but as with the other pieces, reading and thinking about Atwood’s characters and themes in Cat’s Eye is infinitely rewarding.

- Reviewed in the United States on September 2, 2020I’m a huge fan of Atwood’s, and had this book on my Kindle a long time before I got around to reading it.

I both hated and loved this book. Loved it for her beautiful, intricate, evocative use of language ... and hated it because it made me so uncomfortable.

The first quarter of the book focuses on the protagonist’s (Elaine’s) unusual family and therefore her unpreparedness for the “real world” of childhood amongst strangers. She is a true innocent with no natural defenses against the casual cruelty of others. In this, she reminded me so much of myself that this portion of the book was excruciating for me to get through. In fact, I nearly put the book down at this point, with a shudder and sense of relief to let it go.

I did continue reading, however, because Elaine eventually survives childhood and continues through her life, growing a tougher skin but making both good and bad choices along the way, always as a result of her painful childhood and the people who inhabited it.

The final quarter of the book focuses on Elaine’s experience as a moderately successful painter, and was my favorite part. I thoroughly enjoyed Atwood’s descriptions of the artwork (and wish they actually existed) and their relationships to the characters and events in her life. She describes the various vogues and “artspeak” through the years, with a sharp wit that also really struck home.

For those wishing tidy answers, you won’t find them here. However, there is a satisfying ending, and I’m glad to add this book to one of my favorites ... but one which I probably won’t want to revisit any time soon.

- Reviewed in the United States on September 27, 2011When artist Elaine Risling returns home to Toronto for a retrospective art showing, she has mixed feelings. After all, her childhood memories still haunt her, with parts seemingly irretrievable. So what will she discover upon her return?

Buildings that have disappeared, new businesses that have cropped up to replace them, and the memories attached to the once familiar landscape stand out in stark relief.

Elaine's childhood included a gypsy-like traveling about with her entomologist father, and the family camped out in tents. Then would come the months in an almost normal home, but without the normalcy she sees around her. Her fears, her insecurities, and the differences she can feel within must somehow convey themselves to the three girls who call themselves "friends." Is there any other reason for the torture she suffers at their hands?

But years later, only parts of this history remain in her memory, slowly returning in flashes.

The language and images of Cat's Eye were haunting, unforgettable, and reminiscent of some of my own childhood experiences. Who hasn't felt, at one time or another, the insecurity of not fitting in? Who hasn't been bullied or taunted? Reading Elaine's story, from the past to the present, brought these old memories back in full force.

Combined with the visual images of the art showing that depicts many of those childhood moments, the language in Atwood's story had me rereading parts because of the sheer magic of the words. Especially in one poignant scene, when Elaine is remembering a time from her first marriage, as she lies alone in the dark with a sick child while everything is falling apart around her:

"I crouch in the bedroom, in the dark, wrapped in Jon's old sleeping bag, listening to the wheezing sound of Sarah breathing and the whisper of sleet against the window. Love blurs your vision; but after it recedes, you can see more clearly than ever. It's like the tide going out, revealing whatever's been thrown away and sunk: broken bottles, old gloves, rusting pop cans, nibbled fishbodies, bones. This is the kind of thing you see if you sit in the darkness with open eyes, not knowing the future. The ruin you've made."

Throughout this novel, visual images like these totally blew me away with their magnitude. I will not forget this book ever! Five stars.

Top reviews from other countries

Natália PachecoReviewed in Brazil on November 22, 2021

Natália PachecoReviewed in Brazil on November 22, 20215.0 out of 5 stars An excellent novel

Following Risley journey as a woman, a painter, and a mother is simply exceptional. One of the most complex Atwood's works. The interfaces between writing and painting make this novel very unique. Highly recommend!

-

Zufrieden GEReviewed in Germany on September 3, 2024

Zufrieden GEReviewed in Germany on September 3, 20245.0 out of 5 stars Super. Spannend

Super. Spannend. Spannende Leute u. Geschichte

katie carrAmazon CustomerReviewed in Canada on July 12, 2020

katie carrAmazon CustomerReviewed in Canada on July 12, 20205.0 out of 5 stars The story evolves somewhat slowly at times but satisfying read over all.

Shows what life was like post WW2 in Ontario. Couldn't help thinking how some things have changed but much really remains unchanged. Margaret Atwood is a substantial story-teller and she's ours!!

Paul Richard Mc MahonReviewed in Spain on October 8, 2018

Paul Richard Mc MahonReviewed in Spain on October 8, 20185.0 out of 5 stars My favourite Atwood novel

Beautifully written. Very moving and inspiring profound reflections on time, loss and human needs and interactions. One of my all-time favourite novels!

CathReviewed in France on August 29, 2018

CathReviewed in France on August 29, 20185.0 out of 5 stars Parfait

Ecole